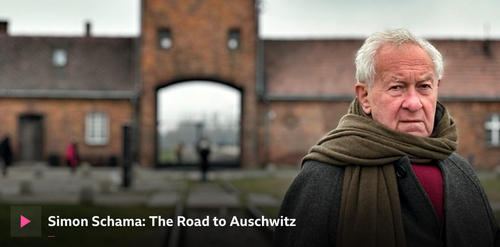

Since Simon Schama is Britain’s best-known historian on Jewish-related matters and one of its best informed, his pronouncements on the Holocaust should be taken seriously. Most recently that means his new BBC documentary, The Road to Auschwitz, released this week.

The “Road to” part of the title is at least as important as the “Auschwitz” part. Schama means it in two senses. It is first of all an account of the horrific events leading up to the horrendous climax of the Holocaust at Auschwitz. His main focus in recounting these events is the key role that non-Germans played in the mass killings of Jews. It is of course well-known that the Nazi Germany bore overall responsibility for the killing but Schama is intent on showing that there was extensive non-Jewish collaboration. Schama succeeds in portraying this reality exceptionally well.

But Schama’s documentary also has a second, related goal. He also wants to help explain the driving forces behind the recent international surge in anti-Semitism, particularly since the pogrom in southern Israel in October 2023. Schama suggests parallels between European participation in Nazi mass killings and the impulses behind the recent wave of anti-Semitic incidents and Holocaust denial. He is less convincing in achieving this secondary objective. If anything he unwittingly ends up underestimating both the horrors of the Holocaust and the challenges involved in tackling contemporary anti-Semitism.

For Schama the Holocaust started in Kaunas in Lithuania June 1941. In Yiddish, the language of eastern European Jewry, it was known as Kovno. That happens to be where Schama’s mother’s family comes from. There, during the Nazi invasion of what was then part of the Soviet Union, the Nazis learnt they would have all too willing foreign collaborators in the murder of Jews. The Germans photographed from the air as Lithuanian volunteers assaulted between 50 and 70 people, mainly Jews, in the town centre. The Lithuanian assailants beat their victims to a pulp with iron crowbars as well as inserting high pressure hoses into their mouths and other orifices. Shortly afterwards the Germans used the excuse of ‘local violence’ to seal Jews into ghettoes before the SS started to liquidate them using Lithuanian volunteers. In late October many thousands of Jews from the ghetto were lined up, made to lie in pits, then shot in the back of the head. This was just one of many mass executions of Jews and others which took place across Lithuania.

It was a pattern repeated, to a greater or lesser extent, in eastern Europe soon after much of it was occupied by the Nazis. This early phase of the mass killing is known as the “Holocaust by bullets”. About 1.5m people were killed by the Nazis in this way in 1941 alone. It was only later that the mass killing by Zyklon B gas in specially constructed extermination camps became the prevalent means of genocide.

Even some countries not occupied by the Germans saw the mass shooting of many Jews by non-Germans. Perhaps most notably Romania, then a Nazi ally, where 48,000 Jews were killed in 10 days in late 1941, almost entirely by Romanians.

The next step on Schama’s journey is Poland, then a centre of Jewish life. Jews there were forced to confine themselves in ghettoes while the Nazis decided what to do with them. Many of the ghetto inmates starved or froze to death. It was in Poland that the network of death camps – extermination camps rather than concentration camps or labour camps – started to emerge.

Complicity was apparent in Nazi-occupied western Europe too but it generally took a different form. Schama shows how the Netherlands used its bureaucratic efficiency, including a sophisticated system for identity cards, to round up Jews to be deported eastwards. Despite its liberal tradition a higher proportion of Dutch Jews were slaughtered than from any other Western European country.

Auschwitz-Birkenau is the last stop on Schama’s journey. There Jews and others from all over Europe were sent to be killed in the camp’s four massive crematoria. Some prisoners, mainly Jews, were also organised into Sonderkommando (special work units) to dispose of the bodies.

Schama rightly argues that the Nazis were particularly focused on targeting Jewish victims. However, he acknowledges other were murdered including communists, non-Jewish Poles, Russians, Roma and Sinti.

The problem with Schama’s approach relates to his parallel narrative. In the programme he asserts that the non-Jewish complicity with the Nazis can be explained by hundreds of years of the dehumanisation of the Jews. He made the same argument in a Jewish Chronicle interview on the documentary where he expressed his “monstrous fury” at everyone involved: “not just the SS. Not just the Germans. It took hundreds of years of bigger dehumanising hatred to make it conceivable that a whole civilisation ends up in smoke.”

His anger is understandable but his use of centuries of dehumanisation as an explanation for collaboration with Nazi killing is questionable. Nor does it explain the recent surge in anti-Semitism. No doubt he could justify his claim. Perhaps he will do so his third and final book in his series on the history of the Jews. But to me it seems inadequate. He would have done better to leave it out, sticking to a description of the terrible events, rather than making questionable assertions.

There are at several problems with the claim about centuries of dehumanisation. First, the emergence of anti-Semitism and the upsurge of pogroms occurred in the late nineteenth century. It was then that anti-Jewish ideas were combined with racial ideology to take the form of modern anti-Semitism. What emerged was a far more potent force than mere prejudice or even hatred alone. It was also from the 1880s onwards that pogroms began to surge in Eastern Europe (The Zionist movement was in turn a response to these trends).

This means there were only decades rather than centuries of anti-Semitism in the run-up to the Holocaust. It is true that many anti-Jewish tropes, such as the idea of Jews as child-killers, date back to the Middle Ages and arguably even before that. But these are better seen as elements of Christian anti-Semitism, part of a religious world view, which were later incorporated into modern anti-Semitism as it emerged as a racial outlook.

Another problem with Schama’s claim is that it ends up downplaying the importance of Germany’s role in the Holocaust. While it is true that non-Germans collaborated with the Nazis, and that is an important subject to investigate, his account underestimates its crucial impact. Without the rise of Nazi Germany and its invasion of neighbouring countries it is hard to imagine the killing of Jews on nearly such a scale. Schama would almost certainly accept this fact but the way he frames his explanation downplays the centrality of Germany.

Germany’s key role is notable because it had arguably been the most culturally and technologically advanced country in Europe. That is not to say that an individual German murdering Jews was any more morally culpable than, say, a Lithuanian or Ukrainian performing the same acts. But genocidal anti-Semitism emerged in Germany as part of a visceral reaction against modernity. It represented an outright rejection of the best the world had to offer at that time. In contrast, Schama suggests the Nazis were responding to the backward desire of millions across Europe, steeped in medieval prejudices, for the Jews to disappear.

The comparison with the impetus behind the recent upsurge in anti-Semitism and Holocaust distortion is also questionable. If it is simply a question of the impact of centuries of dehumanisation why has it surged recently? Why not 10 years ago? Or 30 years ago? The situation in the West today also differs fundamentally from that of Europe in the mid 20th century. Most notably the existence of the state of Israel has changed both the form of anti-Semitism and the ways in which Jews can respond to it.

To be fair to Schama he had no time to explore these deeper themes in a one-hour documentary. He should also be commended for recounting a relatively little-known aspect of the Holocaust. However, he would have done better to avoid making pat assertions about the causes of anti-Semitism. That leaves him open to unintentionally underestimate both the depth of depravity of the Holocaust and the challenges involved in opposing anti-Semitism today.

Simon Schama’s documentary is available to watch in Britain on BBC iPlayer HERE.

The aftermath of the 7 October Hamas pogrom in Israel has made the rethinking of anti-Semitism a more urgent task than ever. Both the extent and character of anti-Semitism is changing. Tragically the open expression of anti-Semitic views is once again becoming respectable. It has also become clearer than ever that anti-Semitism is no longer largely confined to the far right. Woke anti-Semitism and Islamism have also become significant forces.

Under these circumstances I am keen not only to maintain this site but to extend its impact. That means raising funds.

The Radicalism of fools has three subscription levels: Free, Premium and Patron.

Free subscribers will receive all the articles on the site and links to pieces I have written for other publications. Anyone can sign up for free.

Premium subscribers will receive all the benefits available to free subscribers plus my Quarterly Report on Anti-Semitism. They will also receive a signed copy of my Letter on Liberty on Rethinking Anti-Semitism and access to an invitee-only Radicalism

of fools Facebook group. These are available for a 17% discounted annual subscription of £100 or a monthly fee of £10 (or the equivalents in other currencies).

Patron subscribers will receive the benefits of Premium subscribers plus a one-to-one meeting with Daniel. This can either be face-to-face if in London or online. This is available for a 17% discounted annual subscription of £250 or a monthly fee of £25 (or the equivalents in other currencies).

You can sign up to either of the paid levels with any credit or debit card. Just click on the “subscribe now” button below to see the available options for subscribing.

You can of course unsubscribe at any time from any of these subscriptions by clicking “unsubscribe” at the foot of each email.

If you have any comments or questions please contact me at daniel@radicalismoffools.com.