Some key features of contemporary leftist anti-Zionism predate Israel’s creation in 1948 by decades. The radical left has long had a chequered attitude towards Jews at best. At worst it has fully embraced anti-Semitism.

Perhaps the best example is the bogus claim that Jews are, by their nature, racist. Many would trace this charge back to the notorious 1975 United Nations general assembly resolution which proclaimed that “Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination”. The initiative was led by the Soviet Union and supported by the Arab regimes and many other countries then classified as part of the third world. This view had become a central plank of Soviet foreign policy in 1967 – although it was already apparent before then – and was adopted by much of the western left.

What is less well known is that the idea that Jews are by inherently racist goes back at least as far as the early 20th century. Although the language has changed - no-one back then used the language of 'white privilege' - the idea that Jews consider themselves better than others goes back a long way.

To avoid the confusion which is rife in this area let’s start by defining some key terms. Here anti-Zionism is used to describe the view that Israel is the embodiment of the alleged evils of colonialism and civilisation. European anti-Semitism is used here to mean the form of racial Jew hatred which emerged in Europe in the late 19th century. It sees Jews as personifying various supposed evils including speculative capitalism, modernity and sometimes communism too.

Clearly both outlooks have in common the fact that they are anti-Semitic. Both sets of views see Jews as personifying the world’s evils. The difference between them is in the forms of evil with which they associate Jews.

However, the point here is that there are at least two important related similarities beyond the fact that both outlooks are anti-Semitic. Some features which are today associated with anti-Zionism were already apparent in European anti-Semitism.

The first of these is what is often called the left’s blindness to anti-Semitism. Although it might recognise anti-Semitism in some instances – most particularly when it comes from the extreme right – it is all too often denied. This is a topic which Hadley Freeman, a British writer, has written a whole book about. Last May I wrote an article on her book about the left’s anti-Semitism denial. A follow up article looked at a different take on the same subject by Camila Bassi, a lecturer in human geography at Sheffield Hallam University.

But reading a classic text on the rise of racial thinking in Europe, George Mosse’s Toward the Final Solution, I was reminded that anti-Semitism denial on the radical left is not new. On the contrary, it was evident in classic European anti-Semitism. Although it is clear with hindsight that anti-Semitism was a key theme in 20th century Europe the left seldom took the need to challenge it seriously.

For example, Mosse points out that in 1930 the German Communist party had all but eliminated Jews from its leadership and from most of its press. At the same time Germany’s Social Democratic Party was wary of putting Jewish candidates up for public office. By that time the German social democrats were evidently emphasising the importance of the “Aryan Engels” rather than the “Jewish Marx”.

So rather than challenge the rise of the Nazis, who had anti-Semitism at the centre of their ideology, the radical left was adapting to it. With the Nazis on the verge of taking power the German radical left was in effect denying the importance of challenging anti-Semitism.

This is where the charge of inherent Jewish racism comes in. The radical left often combined anti-Semitism denial with the view that that Jews themselves represented a pernicious power. As Mosse puts it: “The tragedy was that a radical denial of racism was combined with the idea the Jews themselves were racist” (p171). In both Germany and Russia it was claimed that the Jews represented a “Jewish-Zionist” or “Jewish-cosmopolitan” threat to Communist ideals of equality for all.

This fitted in with the view that Jews somehow embodied the evils of speculative financial capital. Jews could be seen as part of a class enemy because of their supposed love for money and obsession with commerce. As such they were regarded as an enemy of the proletariat and of other minorities.

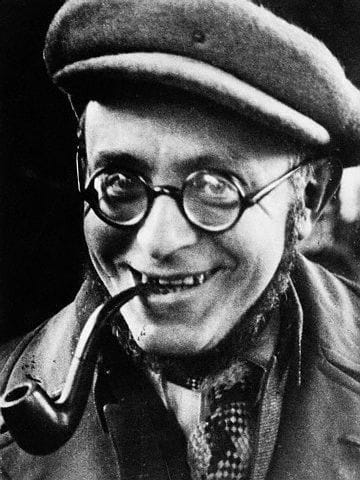

Mosse even quotes Karl Radek (pictured above), a leftist leader with a Jewish family background, who called for an end to both “circumcised and uncircumcised capital”. This was in line with the common radical left view at the time that 'Jewish capital' had to be condemned along with 'Aryan capital'. There was no conception that fighting anti-Semitism meant challenging the ideas that capital could somehow be Jewish in character.

Of course European anti-Semitism went back even before the early 20th century. To be fair there were some leftists in the late 19th century who condemned what they called the “socialism of fools”. Unfortunately those who recognised the importance of challenging anti-Semitism were a minority.

The failure to challenge anti-Semitism was not only a tragedy for Jews although they were its most direct victims. It was also a disaster for anyone who wanted to change society for the better. The victory of anti-Semitic ideology was central to the Nazi’s rise to power in the mid-20th century.

If the need to challenge anti-Semitism had been taken seriously a century ago perhaps some of the worst horrors of the 20th century could have been avoided. Most tragically it is possible the Nazis night not have succeeded in their drive for power.

The past cannot be changed but hopefully the mistake of underestimating the grave dangers of anti-Semitism will face stiffer resistance in the future.

* I am still hoping at some point to tackle Karl Marx’s infamous essay On the Jewish question. However, this is a more complex matter than is generally assumed. That is partly because few recognise it as part of a much wider debate that was going on in Germany in the early 19th century.

Photo: "Karol Sobelsohn" (Radek) by Bettmann is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

The aftermath of the 7 October Hamas pogrom in Israel has made the rethinking of anti-Semitism a more urgent task than ever. Both the extent and character of anti-Semitism is changing. Tragically the open expression of anti-Semitic views is once again becoming respectable. It has also become clearer than ever that anti-Semitism is no longer largely confined to the far right. Woke anti-Semitism and Islamism have also become significant forces.

Under these circumstances I am keen not only to maintain this site but to extend its impact. That means raising funds.

The Radicalism of fools has three subscription levels: Free, Premium and Patron.

Free subscribers will receive all the articles on the site and links to pieces I have written for other publications. Anyone can sign up for free.

Premium subscribers will receive all the benefits available to free subscribers plus my Quarterly Report on Anti-Semitism. They will also receive a signed copy of my Letter on Liberty on Rethinking Anti-Semitism and access to an invitee-only Radicalism

of fools Facebook group. These are available for a 17% discounted annual subscription of £100 or a monthly fee of £10 (or the equivalents in other currencies).

Patron subscribers will receive the benefits of Premium subscribers plus a one-to-one meeting with Daniel. This can either be face-to-face if in London or online. This is available for a 17% discounted annual subscription of £250 or a monthly fee of £25 (or the equivalents in other currencies).

You can sign up to either of the paid levels with any credit or debit card. Just click on the “subscribe now” button below to see the available options for subscribing.

You can of course unsubscribe at any time from any of these subscriptions by clicking “unsubscribe” at the foot of each email.

If you have any comments or questions please contact me at daniel@radicalismoffools.com.